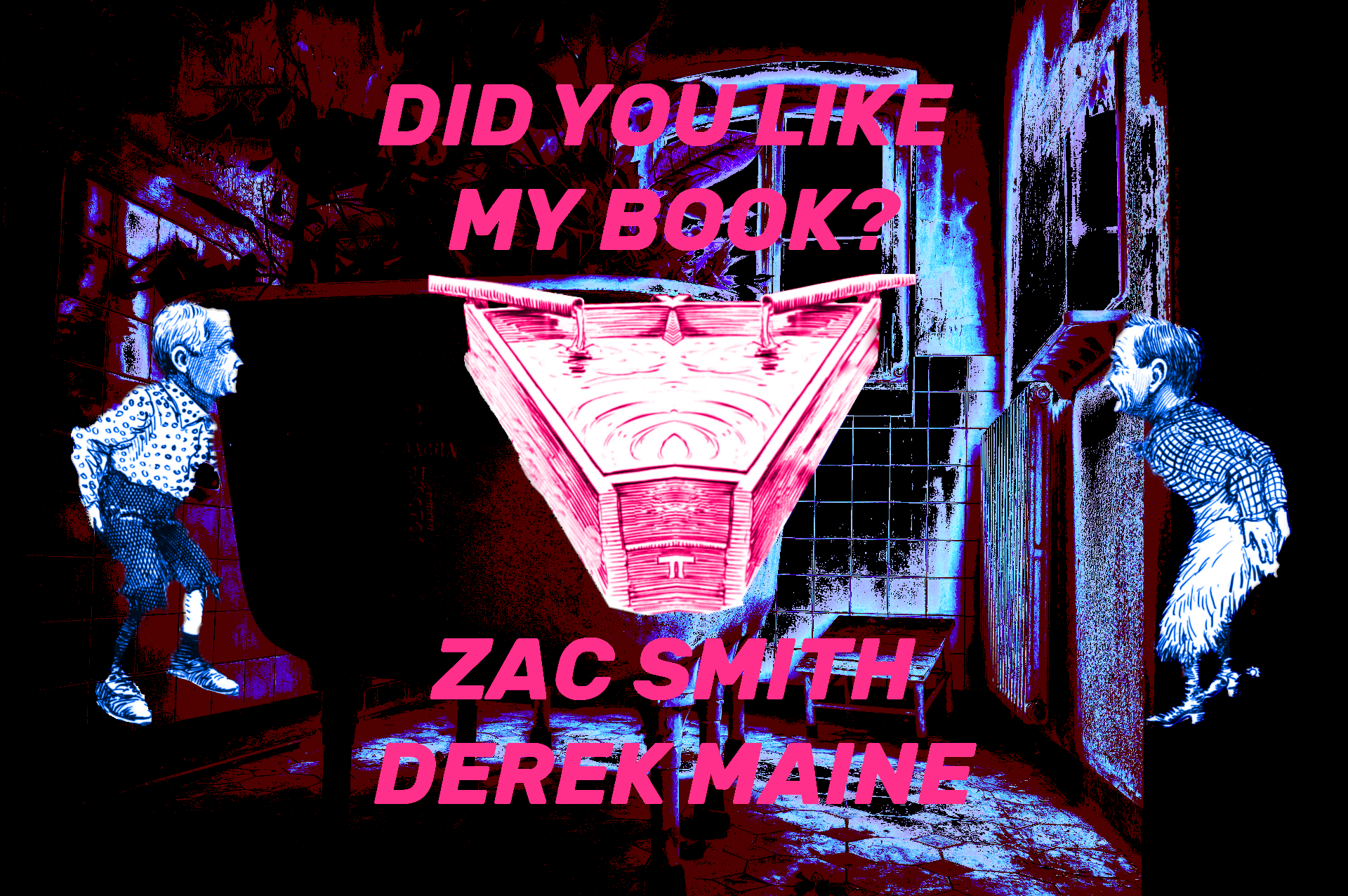

DID YOU LIKE MY BOOK?

I think I was first made aware of Derek Maine through his piece in the second Neutral Spaces magazine. I remember reading most of, if not all of, this issue of the magazine, and feeling impressed by various things in it, including this piece. I think I talked with Giacomo Pope about it, briefly, and how we both liked it. It was engaging, strange, open, sincere without being melodramatic, and about an interesting thing. I like the ending and title, the idea of it being something someone might find while googling for medical symptoms. It was autofiction, or essay, or something in the meaningless space between, and it held promise; I loosely followed Derek after that. He had some story about boxing, I think, which I don’t remember reading. Searching twitter, he has some stories on XRAY and other mags I don’t think I’ve read. He has some book review videos on YouTube, mostly about pretentious literary classics with black and white covers. I like the ridiculous pictures of his bubble bath tray with its book, beverage, and pipe he sometimes posts. I like his self-conscious but, I feel, ‘brave’ forays into literary and gossip review on the Last Estate. We began talking over Twitter DM, briefly and occasionally, mostly about book reviews – our thoughts on them, writing them, what other people think about them, etc. But also about normal, random things: North Carolina, transient alt lit drama, getting vasectomies, and shittalking certain book presses.

At some point I tweeted “[…]interested in trading books with people, if you’re someone who i know and you suspect we haven’t already mutually acquired the other’s books” around the time I was talking with Derek about our experiences with having our books designed/typeset and he said “[…]I am CONVINCED that we will dislike each other’s book and then I don’t know if that would be weird for us because I like you and your outlook and shit quite a lot.” I respected this stance, his willingness to say it, and I felt similarly. We continued to have occasional conversations about the aforementioned topics. I eventually pitched him the idea of this mutual interview based on this experience and other things re: book reviewing that we’ve talked about. But mainly I made myself laugh imagining an interview starting like this:

Q: Did you like my book?

A: No, I didn’t.

So since this is an introduction, I want to write a little bit about why I thought I wouldn’t really like Derek’s book, and all the meta-literary things that go into one’s expectations and prejudgement of a book. I hope some people find the transparency in this helpful in combating their own doubts or confusion, or at least find it interesting.

Here are the three ways I determine whether I’ll buy or read a book, usually:

- The author’s previous writing

- The publisher of the book

- The pr/marketing/reviews of the book

I’ve already mentioned not having read much of his fiction (possibly none – currently unsure what he even has published online as he doesn’t have a website). I like the internet magazine publishing grind in part because it’s a means of finding new writers to read without having to invest in an entire book, and it’s a good way to see what someone is experimenting with or leaning toward in making a book when they do have one come out. Without much published online, especially not, as far as I could tell, any excerpts from Characters, maybe, I had no reason to think this book would be especially good – or bad, for what it’s worth. I just didn’t know what it would be like. I had to rely on other things to determine whether I’d like it:

- The author’s previous writing

- The publisher of the book

- The pr/marketing/reviews of the book

Having addressed (1) above, I will continue on to (2).

A good publisher is, to me, one that curates a type of book unique to, or reasonably predictable of, itself. If you read a couple books from a press you should, I feel, have a good sense of whether you’ll like another one on the press.

When you follow along, you can see when someone is probably going to put out something good (to you, based on your tastes). You can see who is really attempting to push a boundary, play with a form, or just compile whatever they had sitting around. From the publisher angle, you can see when a book is a formality, or a gamble, or a cash grab, or a backscratch, or a pity handjob after a bad date. You can see when some authors are treated more like a mark than others, the nobodies who are more than happy to buy their pressmate’s books and write glowing reviews in exchange for their spot in the pyramid and a few ‘why not’ purchases from the crowd. You can also speculate about the pipeline of people who pay out of pocket for edits or workshops from certain well-regarded authors and then get a book on certain presses. You see who tries to cut their teeth engaging with the scene in an earnest way, and you see who thinks they’re above it all, who think they’re sitting on the golden goose of a transgressive novel, who think they’re special, or are told their special, or really have no idea what they’re doing but did something interesting, maybe, anyway. You can’t help but invent and project categories on other writers, on presses, on the book promo cycles. Or at least I can’t. And when I saw Derek with an ExPat book, I had my thoughts about what that meant and whether I’d like it. And when I read his interview about the book on ExPat, I had even more thoughts about it (more on this later).

Derek’s book is on ExPat Press – a publisher uniquely heavy with baggage for a variety of reasons. ExPat Press is, like most little presses in this corner of the internet, one person: Manuel. He’s courted drama, run through several assistant editors, had a few authors pull their books, and suffered wave after wave of random griefing on Twitter. But I’m not gonna hash any of that out. I want to focus on the personal and aesthetic, for me, here, only. I’ve read and enjoyed several ExPat books (Calvin’s, bibles’s, Dale’s) and felt ambivalent about or disliked some others. Manuel curates, in general, a vibe of pretentious edginess. Sometimes I think he finds something great, sometimes I think he’s just keeping the wheel spinning to stay relevant. He’s also done the old follow-then-unfollow-when-I-don’t-follow-back-on-Twitter thing with me and has published books by at least two authors who have publicly, beligerently shittalked me and my writing on the internet. So I’m not squarely on team ExPat, but I’d probably rather read an ExPat book than an Okay Donkey book. Anyway, Manuel’s approach to writing completely opaque and uninformative synopses makes it impossible to discern what might be worth picking up if you don’t already follow whoever it is on Twitter (e.g. Derek’s book is described as a ‘frame narrative in fluid relief’ and a ‘symbiotic dyad between consumer and creator,’ among other things). 2022 was also the year ExPat seemingly published a book every few weeks, following a manic year or two of publishing something on the website every day – a good move to build up an audience and drum up interest, source some new excited players to churn through, and flesh out the catalog a bit and see if something sticks. I mention all this as part of a grander discussion of what goes into buying a book when you’re a part of the very group of people making and selling books. If I were to rely on just the publisher to discern anything about Derek’s book, by mid-2022, I wouldn’t have much to go on. Statistically it would be another Dennis Cooper ripoff (I have not read anything by Dennis Cooper), but, based on what I knew about Derek, it was probably not. I couldn’t tell you whether Manuel published it because he loved it, or because Derek’s his friend, or because Derek has a certain amount of clout in the ExPat sphere, or some other reason ranging from cynical to kind.

- The author’s previous writing

- The publisher of the book

- The pr/marketing/reviews of the book

So the last thing I had to go on is the press/publicity: goodreads reviews, word-of-month, interviews, this kind of stuff. ExPat (like any other self-respecting indie press) doesn’t have a PR wing, doesn’t send out physical ARCs, and doesn’t have a distributor (only one book is available via Amazon KDP, as far as I know). So there’s no review in The Washington Post to read and learn whether it’s content worth consuming. They’re not showing up in some Lithub listicle with all the book blob books. Some aren’t even on Goodreads. But Characters by Derek Maine is, and as of October 14, the Goodreads page for it has 10 ratings, 3 reviews: 4.7 stars. Sheldon Birnie gave it 5 stars (he gave my book 4 stars). Word-of-mouth-wise, no one I talk to has read it (I talk to very few people), so there’s no word, no mouth. That leaves his one interview, on Expat itself (a standard thing Manuel does, graciously, for his authors). In this interview, Derek comes off as both self-conscious and pretentious (a negative), obliquely shittalks Inside the Castle (a positive), makes a couple jokes (some land, some do not – a wash), quotes both the Bible and Frank Lloyd Wright (pretentious – negative), mentions that other famous/dead authors feature in the book (pretentious – negative), and suggests that the book is for ‘re-readers’ (pretentious – negative – [x] [x] [x], three strikes, buddy). And further, this last thing made me scoff – why assume a single reader, let alone a re-reader? We are not entitled to anyone giving a shit. You have to leave that at the door when you get into indie lit twitter. This is a book by someone un-humble, someone obsessed with the ‘greats,’ who desires very transparently to be viewed as a serious, literary writer, was my general takeaway. I had no desire to read it (there are many books I have no desire to read). And I didn’t plan on buying it.

But then I started talking with the guy. And we got this little scheme to talk about how we will probably fucking hate each other’s books. And here is where I pretend to play along with the little Last Estate bit about them living in a house together. He invited me over. I arrived, blindfolded, after a suspiciously short drive from the Toledo Greyhound station. He gave me the tour. Cooked us some hush puppies. William is watching me, nodding, as I type this. Hello, I nod back. Hello, he nods again. His smile is infectious. Stuart is wearing a tank top, always in the tank top, always gallivanting sans sleeve. Always interrupting to ask if I, too, came prepared to tank it up with him. Gabe is taking a shit, I can see, from my little writing desk – why are there no doors here? – and it stinks. I hate this estate. And so on. But now I’ve bought the book (together with Calvin’s new book – will it be as good as Family Annihilator? – Pitney Bowes, praise be, deliver unto me, etc.) and I’ve even read it in their little library. It’s very quaint. Very little color. Very few books, even. And now Derek has drawn us both a bath. Oh, Christ. We are to submerge together, he says, to do the deed. It is quite a large bath, I note, despairing. A big bath for two big boys, he assures me, smoking his marijuana pipe. We get into it.

***

Zac Smith: Did you like my book?

Derek Maine: So, we’re just going to get right into it? No foreplay. Rip off the band-aid.

ZS: I think this question is the conceit of the interview. We should give the reader what they want.

DM: I didn’t like it.

ZS: [laughs] Nice, that’s good. Thank you. I appreciate you saying you didn’t like it.

DM: But I, at least, didn’t like the book for different reasons than I expected. Ultimately, I think of it like this: when I was playing in bands and going to punk shows, I had friends that got really into metal. Speed metal. Death metal. Two kick drum metal. All kinds of metal.

ZS: Yeah, sure.

DM: I can’t stand metal.

ZS: [Laughs] Of course.

DM: It’s not for me. But, like, it was ok that I didn’t like their metal bands. It didn’t affect our friendship or our respect for each other. It was just understood, “oh, we have different tastes.” For some reason that kind of divergence in taste or style doesn’t translate the same to literature, or a literary scene. You either love something, and gush accordingly, or maintain an uncomfortable silence – a kind of truce between artists.

ZS: I like this interest-in-metal comparison and feel like I’ve experienced that with people in similar ways. And you’re right. We’ve talked about this before. If someone loves a book, they tell people. If they hate a book, they just ignore it. There’s little interest in negative reviews.

DM: But your book is good.

ZS: [Laughs] You don’t have to be so complimentary.

DM: No, it’s clearly a well-crafted, thoughtful piece of work. I just don’t like it. There are plenty of things that are objectively good that I don’t care for.

ZS: That’s good. Thank you. But I feel like that’s a contradiction – if something were objectively good, you’d have to like it, by the objectivity of it. I don’t think either of us really believe in the existence of objectively good art. I think you mean something else, maybe technically proficient.

DM: That’s exactly right. Technically proficient is a good way to put it. When I was doing this interview in my imagination, before it even started, I thought about making a joke about how I didn’t find any spelling errors. “It was a really good book. Like, everything seemed to be spelled correctly.”

ZS: [Laughs] Yes. Success. Thank you. But for real, in contrast, maybe, I like that your book spends a lot of time looking back at itself and the “author,” like, about the formatting, the structure. There are sections of, I assume, free-writing, that were probably mostly unedited.

DM: I’m not sure how technically proficient my book is. I’m not a very technical writer, I guess.

ZS: I think you’re a proficient writer, Derek. You use a lot of techniques, too. You’re good.

DM: It was all heavily edited though. The sections that you refer to as free-writing have a narrative reason to exist in the way they do and there is supposed to be a legitimate question of authorship during those sections. I fought for a lot of my mistakes.

ZS: I wanna clarify that I’m not saying your book is badly written or anything. But yeah, I think it has, and conveys, in its writing, a fascination with the idea of something being written well or written poorly, with something being written with passion versus something written with precision. Does that feel accurate?

DM: Yes, I think Characters is fascinated with why someone writes, and the purpose of literature. Particularly since literature has been pronounced dead for thousands of years. Or at least fifty.

ZS: [Laughs] Who pronounced literature dead? I don’t know enough about literature to get that reference.

DM: It was a common refrain for most of last century, I think. Radio killed it. Then television. The Internet. Our desire to read books waned, reportedly. Less and less readers, supposedly. Then there is the evergreen question of the purpose of literature, which is always a battlefield, I feel like. There’s a contemporary critic I really like, Christian Lorentzen, who has argued literature is essentially a hedonistic activity. I like the sentiment, but don’t fully agree. I actually think literature in this century will be tremendously valuable. It’s the last place anyone would ever look.

ZS: Yeah, I’m with you on that. Jordan Castro said something in an interview that I liked, sort of in line with defending this selfish or hedonistic view of art, in that in a hundred years we’ll still need art from our time in spite of whatever social or political movements are going on. You always need art for its own sake, because you need beauty. Not that either or our books are beautiful. But you know what I mean. But related to purpose or value in writing, people in our little world like to put a lot of value in authenticity. Do you think our differences are part of a performance of authenticity? Is one of us writing more authentically than the other?

[15 minutes pass in silence. Derek lets out some of the water and runs the hot water for a minute, adding bubble bath]

DM: I don’t think of writing in terms of authenticity. One of the reasons it has taken me so long to respond is me turning this question over in my head, and I feel satisfied I’ve found my answer: I don’t know if one of us is writing more authentically than the other because I have very little interest in the concept of authenticity.

ZS: That’s good. Nice. I like that. Well, I liked your book. Or I liked a lot of parts of it. I thought it was fun, leaning into things unselfconsciously in spite of the emphasis on being self-conscious. You mentioned just now, and also in the sort of post-modern parts of the book, that you fought to get it to look or read a certain way. And, like a lot of people, I assume, you’ve also mentioned having written and abandoned a lot of writing. I’m curious about that. Why this book? What changed? And do you like how it turned out?

DM: That’s a good question. Well, I did make a conscious effort to publish some short pieces online, around 2020, during the initial wave of the pandemic. And that sort of, as you know, places you in this strange literary community – cyberwriting! Before that my only public interaction with literature was making these YouTube book review videos because I was lonely and wanted to talk about books I loved. So I’m trying to get these stories published and getting to know the landscape, as it were. I didn’t think I was writing a book for the first 5-6 pieces, and I know that’s obvious to the reader. Then I started asking myself why I wanted to be published for a dozen – if you’re lucky – people to read a story, and what I was getting out of it. And then this thing happened, it’s in the book, where I lost a friend over something I published. I don’t have a lot of friends.

ZS: So that really happened! I felt stupid coming in and asking that, since the book plays with this question of what is real and what is fiction. That’s heartbreaking, but relatable. I’ve experienced similar things.

DM: Right. So I had to ask myself some difficult questions. And the only way I could figure out how to answer those questions was to write, and so Characters came out of that. I finally found the answer and ended the book. It’s the last line.

ZS: Sounds like you’re happy with it. That’s good. You should be.

DM: What about you? Did you like your book? Does it bother you when people don’t like your book?

ZS: It would be stupid to assume or hope that everyone likes something. It doesn’t bother me. I believe, generally, that for something to be something that someone loves, it has to also be something that someone else hates, and something someone else considers just okay, etcetera. I do like my own book, but I haven’t reread it in a long time.

DM: I agree completely with what you said about something needing to be loved by some, and hated by some, and passable or just ok by some. It’s funny that “experimental fiction” is a label that gets some traction, but you rarely hear about our literary experiments failing. Most experiments do fail. I’m not saying your work is experimental. I wouldn’t. Insomuch as that word means anything (like transgressive, another absurd, meaningless tag) I wouldn’t classify Everything is Totally Fine as an experiment. I could see handing this to a really depressed teenager living in a nondescript suburbia and saying, “everything might be exactly as awful as you imagine, but at least you’re not alone and you can always order a pizza.” I could see it being someone’s comfort food.

ZS: It’s funny, Giacomo [Pope] and I wrote about this exact thing – about whether or not ‘experimental’ writing is ever really reviewed in terms of the hypothesis and result – in an essay for the print version of Two Million Shirts. But I think people have different understandings of what they mean by the term. For me, probably all writing is an experiment. I know what I was trying to do, what I thought might happen by writing certain things a certain way. But you’re right that people generally use “experimental” to describe stuff that looks weird. Do you consider your book experimental? I think it is, right? In both meanings of the term, probably.

DM: I think my book probably is experimental in both meanings of the word. For as much autofiction and metafiction that exists and as seductive and nauseating as it is to both writers and readers, I do think there are still some tricks that haven’t been fully explored. I tried to fuck wth some of those things. Memory. Consciousness. Artificial Intelligence. “What is real? Does it hurt?” The screeching modern experience of too much sight, too much sound, too many characters coming in and out of view often with no introduction or attribution. Proving to myself that I am real.

ZS: It’s funny, I think most of what you’re saying applies equally to our books. Or we could have both said that about our own book and been right, aside from the artificial intelligence thing. But the results are very different. Relatedly, I’m curious about what reasons you thought you would dislike my book vs. the actual reasons. You mentioned thinking it would be “twee” when we talked before. Is my book twee?

DM: Not at all! [Laughs] I don’t know why I kept thinking about this but I had a vision of Wes Anderson movies in my mind when I thought of Everything is Totally Fine. And even then, twee is kind of the wrong word for what he does but it’s cute, right? Even when it’s really, really great like The Life Aquatic or The Royal Tenenbaums, it’s still cute.

ZS: Yeah, his movies are, like, charming. There’s good color and silly coincidences. But there are also scenes about suicide and heartbreak. I like his movies but haven’t watched one in possibly more than ten years.

DM: Anyway, I don’t know why, but this was the mental image I had constructed, and I was completely off-base, of course. I didn’t like the book because I don’t enjoy detached, slacker irony and I thought your book did that. There was also an element of magical realism that I’ve never been interested in. The kind of thing where someone will be doing a very regular, relatable thing and then a sinkhole will open up and look at all the crazy, unbelievable stuff that’s happening and then we circle back to the regular, relatable circumstance.

ZS: People have described it as ironic and whenever people say that I wonder if I know what irony means. Maybe I’m stuck on some specific definition of it so I’ve since Googled “irony” and thought about it. I think my book is unrionic in the literary and Greek tragedy meaning, according to the Google definition. But it does seem to be ironic according to the other definition, related to sarcasm and dryness. In any case I understand. Again, I see our books as sort of opposites along this spectrum here. I think your book is written to be very earnest and realistic — in spite of the sci-fi elements, I guess — in a way that can come off as dramatic or cloying, whereas mine is written to be very ironic and absurd in a way that can come off as smug or cynical. We both look at death, for example, but write about them in opposite ways, like I’m trying to make the reader laugh, and you’re trying to make them cry. Do you consider my approach to be a lesser approach? Do you think all great literature needs to be dramatic, tense?

DM: I don’t consider it a lesser approach at all. I consider it a more difficult approach. It’s cliche at this point but I think it must be true that writing something funnier is much, much more difficult than writing something sad. But even humorous, absurdist work needs tension. There is an unreality with your work in this book, a cartoonish element where suddenly the physical rules of the natural world are often upended and an impossible, absurd thing will take place. But the joke never landed with me, for whatever reason. I think it might have had to do with how weary the characters were – how indifferent they seemed. It didn’t seem to matter that much to them, at least how I read it, so there wasn’t much for me to be invested in. I felt like I was in a world that was already over. Everyone and everything was resigned.

ZS: Yeah that’s fair. That’s exactly the tone it landed on. I think this speaks to our different worldviews. I do think it feels like the world is already over. The world does feel cartoonish, and it does feel to me like everyone has resigned. So that felt funny and interesting to me. A sort of boring end of the world. But yeah, in your book, everyone is very invested in something. Life and death are still dramatic. You presuppose the world will go on, that people will care. It’s focused on legacy, past vs. future. It’s full of tension. So to borrow your phrasing, that to me was the unreality in your work. I’m enjoying this.

DM: Another thing I didn’t like was that your book is a collection of very short pieces.

ZS: [Laughs]

DM: The only author I really enjoy that does that is Lydia Davis and with her I read her collections slowly, over a long period of time. It’s a book to pick up, read a story, and sit and think about it or just mull it throughout the day. When you read it straight through, like I did with yours, the pieces pile up on you and lose the punch of surprise. You lose the effect of short fiction.

ZS: But that’s not the fault of my book, is it? That’s on the reader. You choose to read Lydia Davis that way.

DM: I am certain I would have enjoyed Everything is Totally Fine more if I had read it slowly. I didn’t speed through it by any means. I read a few pieces over a couple times. There is a piece titled “Doors” that was fantastic – something out of an old Rod Sterling Twilight Zone episode. I wish it had been longer, more fleshed out, more said about the effect it had on the character and also more done with the conceit. I felt this way about several pieces. The conceit would be interesting, even novel. The character would react to an unbelievable circumstance with a kind of shrug but there was no further exploration. I imagine this effect is on purpose. I suppose you want the reader to linger on your stories in their mind, maybe filling in their own absurdities and neurosis into the world you’ve briefly drawn. I want to empty readers out. I want to be emptied out, as a reader.

ZS: But I mean, your use of fragmentation, the jostling of narrators, changes in point of view. You’re also asking the reader to fill things in. You’re not fleshing out this world. It does that Infinite Jest thing where it’s like a satellite dish. Everything on the page is pointing to something off the page. Your characters don’t shrug, but a lot is also left unexplored. I just can’t think of our books as contrasting that heavily here. It reduces to just: we’re both making expectations of the reader. Just different kinds, or we assume different kinds of readers.

ZS: But it’s funny because your book has a central theme on the author-reader relationship. So I think your book is also sort of the opposite of mine in this way, too. It needs to be read within a short period of time, I think, for it to be effective. If you put it down for a week, it might be hard to pick back up, especially when it starts teasing the narrative-within-the-narrative.

DM: Do you have a reader in mind when you write? Do you write for yourself? Do you laugh at your own jokes? Is there joy in creation?

ZS: I don’t have a reader in mind when I write. Maybe it’s just for myself. I like making myself laugh and wanted to write stories that felt new and funny to me, maybe just me and some close friends. I have since read various things — from a long time ago, in translation, like The Bridegroom Was a Dog by Yoko Tawada — that feel like things I tried to write in different ways. And that’s been exciting and kind of validating, but also unsurprising. It’d be dumb to think I’ve done anything new. Anyway, the joy of creation is the only joy, really, I think, yeah.

DM: What about publishing? Is there joy in that?

ZS: I have been involved in publishing at varying parts of the process and it mostly sucks. Parts are fun, when you can get into a groove. But overall it’s a lot of unfun work. The only good part, I think, is connecting with people, doing stuff like this, talking about books and writing. What about you? How is it? How was it?

DM: It’s…ok? I don’t know how to feel about it. Very, very early. I tell everyone this but literature lasts a long time. And I published with a very independent press. You can’t order my book on Amazon. It’s in maybe three bookstores across the country. People sometimes message me asking for a copy, which is very nice, and I have to just send them the link to order it from the publisher because I only have one copy. Maybe I could have more but I don’t need to. So in a lot of ways it feels like I haven’t participated in the publishing of my own book. I launched it by reading to my phone’s camera, alone, in an empty Red Lobster parking lot on Buck Jones Road.

ZS: You wanted to make a book but you didn’t want to sell it. It’s the never-ending struggle. Sure. But clearly you’re preoccupied with Literature, capital L. You’re fascinated by its legacy, how it can endure. And that’s usually a function of the publisher: who keeps it in prin, who makes it available, who gives it legitimacy to the press, big or small. What were you hoping for? What would you recommend for other debut novelists?

DM: I don’t know what I was hoping for. Readers, honestly. To come into that relationship, that sort of intimacy between consciousnesses separated by time and space, from the other side. I recommend debut novelists not send out their manuscript blindly and wildly but find a publisher they connect with artistically. I would recommend they constantly ask themselves why they want to be published, what purpose it serves in their life, and let those answers guide them.

ZS: I want to get back to one of the first things you said, about the mental image you had before reading, because that’s interesting to me and the main thesis of my introduction (which you haven’t read yet). I’m curious about what your experience was like constructing that image of my book before reading it, why, for example, you expected a Wes Andersonian kind of thing. What did you know about it, what did you not know, what had you thought about me, what led you to think that about me, and so on. I’m curious about this because we live online in this soup of familiarity and distance. We’ve been known to the other for a while, but hang out mostly in different circles. We have preconceived notions about eachothers’ book publishers, our friends and their writing, all this stuff. I’m interested in hearing more about what that composite image of my book was for you.

DM: I didn’t know much about your book before reading it but I knew you had written a collection of poems about barns. I knew that book came out on Clash which has some pretty big releases. I knew you were publishing this book with Muumuu House. I knew you liked shoegaze music. I knew you as one of the guys behind Back Patio Press – and as you know I reviewed and loved Cavin Gonzalez’s book I Could be Your Neighbor, Isn’t That Horrifying?

ZS: A beautiful book.

DM: And I thought you seemed fed up or cynical about online literature, which is understandable. But I also knew you were giving a lot of yourself and your time and your energy to the literary scene. I don’t think any of us have a very good sense of how we take the scraps of incomplete information we have about a stranger on the internet and create our fragile mental images. I thought your writing style in tweets was strange, sort of whimsical with a bit of a nasty edge. How I took all of that, and whatever other bullshit I’ve forgotten or buried, and decided your book was going to be twee, is a mystery to me. But it’s not, of course. It’s metal as fuck.

ZS: And you can’t stand metal.

DM: [Laughs]

[Gabe knocks on the door – he must shit, again. The two authors emerge from the tub, matching swim trunks glistening in the candle light. Their ding dongs, outlined against the dripping and taught polyester blend, are very large. Derek removes his sunglasses. It is very good. Everyone likes what’s happening. The end.]