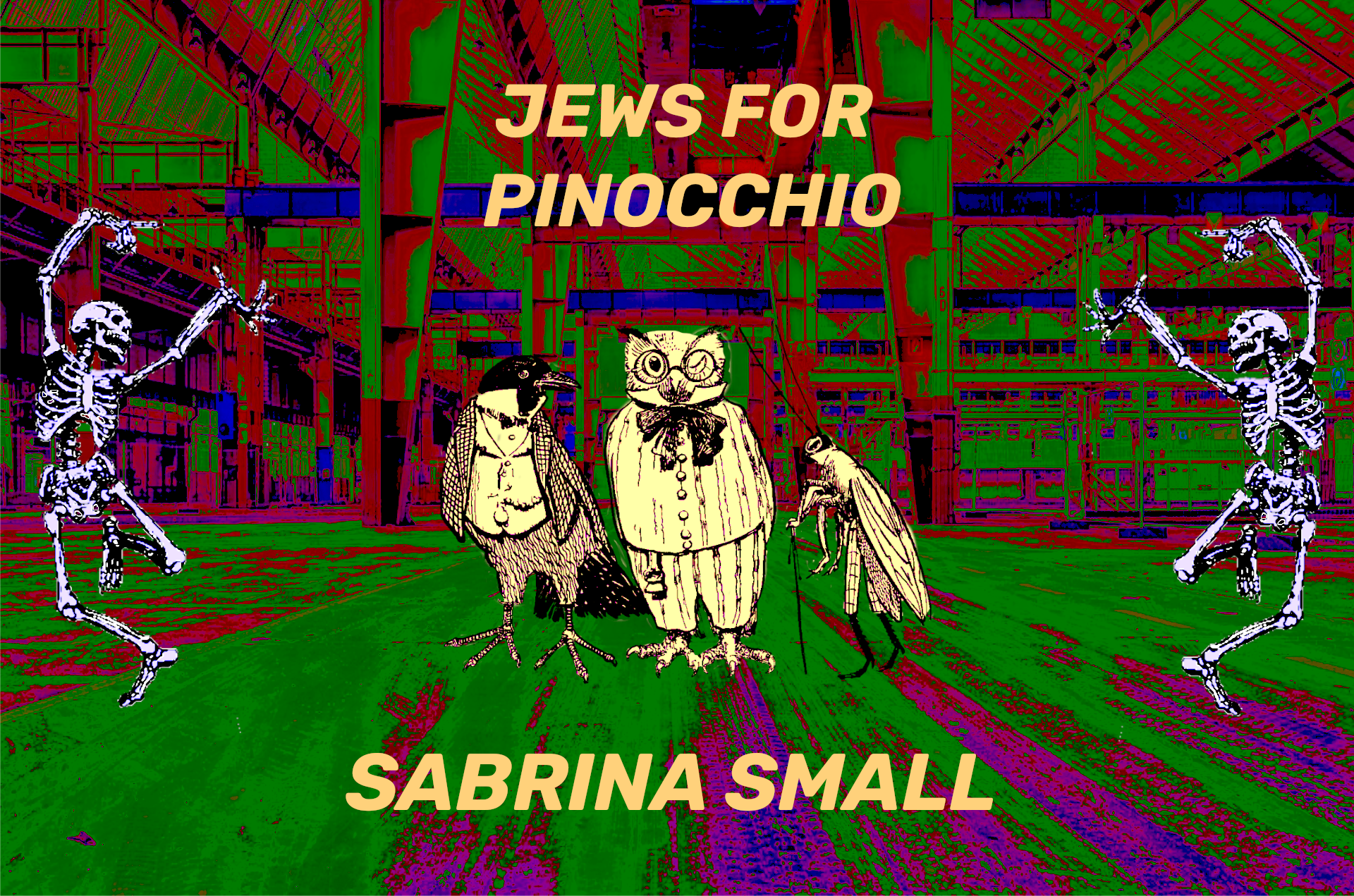

Jews for Pinocchio

Her name was Leah. She was quiet and clearly unpopular. There was a rumor she shit her pants. I definitely didn’t question the validity of this rumor. Leah looked exactly like the kind of 9 year old who would shit her pants. She was the first and last Jew for Jesus I ever met. I knew this because she advertised. She wore a purple t-shirt with a big white Jewish star on the front and the words “Jews for Jesus” encircling the star like a toothless pentagram. I feared showing her even an ounce of friendliness, in case she was recruiting. As far as I could tell, there was no serious consequence to my open disdain for Leah. What kind of bisexual choice is Jews for Jesus anyway? What kind of cake was she trying to have and eat too?

April Windsor drank milk with dinner. When I went over to her house, the beverage options were off. Milk with dinner, and for breakfast, orange juice that came out of the freezer. Friday sleepovers were preferable at April’s house. Saturday sleepovers meant I went along to church on Sunday. Church made me anxious. I had such limited exposure to Christianity in general, Lutheranism in particular. There were more worshippers at April’s church on a random Sunday than I’d ever seen at Rosh Hashanah. But still, my myopic LA Jewish bubble convinced me that Christians were the minority.

April went down to the stage (pulpit?) to get her wafer with the other believers. The preacher set it up perfectly. This guy was a real sultan of segueway. He said, “Anyone who wants to come forward for consecration is welcome.” Consecration made me think of the orange juice from concentrate in April’s freezer. Some words are all process and therefore unknowable. I can’t relate to consecration, collision, consternation. Those are what my dad would have called $10 dollar words.

All religious services make me extremely hungry. The marked absence of food is what does it. I get nervous in any space where food isn’t present. In my office-worker days, I was that bitch with a full fucking snack drawer. Anyway, I was dying to know what that wafer tasted like because April said it tasted like nothing and that is just impossible. I asked her, is it good though? She couldn’t answer me. I was 3 or 4 trips to her church deep, when I just rolled up with April, knelt and got one myself. No one stopped me but I felt like they should or they would at any moment. I wondered if the wafer would burn my tongue. A wafer tastes like a cheap ice cream cone, by the way.

It’s the end of the year. From the middle of December until the new year, it’s impossible to do anything but bide my time. I’m not a hero. I’m not about to start some ambitious project on December 18th. My days are purposely empty. I can afford this lifestyle because I was a good saver during my office-worker days. I can live off the fat rendered from years in that ergonomic chair. What did I do all day for 10 years? I typed synergistic. I typed coopetition. I typed innovation ten times into every presentation. Now I write what I want. My time is mine to squander until I have to pick up the kids. It’s 1pm. I pop a blue gummi and put on Guillermo del Toro’s Pinocchio.

Getting high and watching animation is one of life’s reliable joys. Outside it is -7 C, the kind of cold that erases your chin from your face. I am on the couch with a thick duvet covered in brown and pink roses. I embrace the present fully. I open myself up for immersion and escape.

By the time

Master Geppetto made Pinocchio,

he had already lost a son.

Now this was quite a few years

before my time,

but I learnt the story.

And then it became my story.

Geppetto lost Carlo during the Great War.

They’d been together only ten years.

But it was as if Carlo had taken

the old man’s life with him.

The first lines of the script–spoken by Ewan Mcgregor as Sebastian J. Cricket–are a poem about grief. They are also a writer’s introduction, a masterful grounding in time and place, and a promise that nothing about this film will be light and easy.

The appeal of source material, of ancient stories, is that they include everything. All the major human themes with none of the irony or metaphor that stymies so many modern productions. Pinocchio is an ancient story. When a story gets old enough, it’s basically a religious text. What’s the difference between Adam and Eve and Beowulf? Between Abraham and Faust? Between a story where a guy makes loaves of bread into fish and a story where a boy is made out of wood and grows his nose whenever he lies? Can I believe in Pinocchio? Do I? Is this the only chance for someone like me? Someone without a religious community, to have an ecstatic experience?

I’m drawn to mainstream films that present a version of religion that’s carefully God avoidant. In these productions, death is a place where arbitration occurs, where a hierarchical network is hinted at, and lessons must be learned to move on. Heaven and Hell are only hinted at, sometimes not mentioned at all. There might even be a celestial figure or two, but these films are purposely distancing themselves from recognizable religion.

The first example that really spoke to me was Albert Brooks’ Defending Your Life. After getting hit by a bus, Brooks finds himself in a well oiled purgatory where he’s assigned a caseworker and must have his life’s choices examined by cosmic judges. This stopover of the afterlife is depicted as an Orlando resort, with trams escorting the newly dead to the hall of past lives (where you can see who you’ve been), restaurants (where guests can gorge themselves with no consequence), and a schlocky comedy club (where a lounge singer does a mediocre rendition of “That’s Life”).

I was 11 when I first saw Albert Brooks in an ill-fitting toga, fall in love with Meryl Streep during their stopover to eternity. It’s clear that Brooks has a few more rounds to go on earth. He lived a weak-willed, unconfident life and learned very little about the meaning of existence. But during his weekend, he grows a big pair chasing after Streep, his soulmate. In the end, the star crossed lovers are on different trams, headed to different destinations but Brooks does not go gently into that good night. He leaps from his tram to Streep’s and because of this insane act of last minute bravery, the cosmic judge rewards him and lets him join Streep in the VIP area of the afterlife.

Albert Brooks shopped at the same Gelson’s as my family. I saw him in the produce section shortly after I saw Defending Your Life. I asked my mom for a pen and paper and she fished it out of her purse. Then I asked Albert Brooks for his autograph and he said, “Why?”

Lying comes naturally to me just as not believing in God comes naturally to me. It’s possible the two concepts are related. When I was just a little whippersnapper, the guitar playing rabbi took a beat between Hebrew hits to tell his young flock about HASHEM. HASHEM is all around you. HASHEM is the trees. HASHEM is the wind. HASHEM is your own breath.

Who is this for, I wondered? Who’s actually buying this junk? What kind of nursery rhyme bullshit is this? Here we are, tough Jews, bearers of our ancestors’ stories. As Woody Allen put it, “My grammy never gave gifts. She was too busy getting raped by Cossacks.” So who does this long haired hippie rabbi with his fucking denim vest think he is? God is bullshit. God does not exist. God is a fantasy for people who are too weak to cope with the brevity of life, which doles out one joyful moment for every 400 hundred shitty ones, if you’re lucky.

Lying is just picking up on your own wish fulfillment or tuning into the wishes of others. I can make someone feel great with a soft lie. Most of us can.

Significant lies I’ve told:

-

- That my mom died in a car accident. I was in kindergarten. My dad came to pick me up and my teacher hugged him and said, “I’m so sorry for your loss.” I know this story because it’s been repeated to me. I don’t remember doing it myself.

-

- That I didn’t steal 80 dollars. I was 12. My parents left for a vacation. They left us with my cousin and they left an envelope full of cash. I took 80 out of the envelope and bought candy for my sisters all week. Do you know what it’s like to flash that cash at the gas station and walk out with a bunch of Laffy Taffy? It’s fucking baller. My cousin caught on and he told my parents. They confronted me and I denied it. I denied it forever. The last time my dad asked me about stealing the 80 dollars, I was in my late 20s. I denied it and he punched me in the shoulder, jovially. Begrudging respect for my method acting.

-

- That I used to date Zach Galifinakis. I briefly joined the English language comedy scene in Berlin. It’s a small scene. I did a set that was electrifying about the romance of anal sex. I plummeted after that. I didn’t even bomb. It was more like I just couldn’t get back on stage. But the comics let me in and I wanted their admiration. I chose Zach Galifinakis because I think I could get him. I’m hotter than he is. I’ve fucked lots of Gakifinakis types. I told this lie in an off the cuff way. I kept it subtle and mysterious because that makes it more believable. Everyone believed me and my Galifinakis-adjacent status kept me in the group despite the fact that I was not producing anything or performing. Eventually I found a serious boyfriend and dropped out of the comedy scene.

Pinocchio is an unruly child. He makes life difficult for his father. He breaks things. He doesn’t listen. He lies. In del Toro’s version of the film, Pinocchio’s curious fumblings are amplified. No one is sure they want him around. Gepetto calls his ersatz son a burden. Pinocchio is ashamed. He wants to make his father proud. He goes about it all wrong. First, he joins a corrupt circus, led by the heartless Volpe (voiced expertly by Christoph Waltz). At the end of his first show, Pinocchio is overjoyed by the love and acceptance of the audience but Gepetto is not proud of him. He is mad Pinocchio did not obey him and go to school. The human cost of blind obedience is an ongoing theme: obedience to fathers, a soldier’s obedience to his commander, even obedience to cosmic rules. Pinocchio questions all of these rules, breaks most of them.

Pinocchio is a boy who can’t die. He goes to an afterlife of sorts, and succumbs to a ritual as quick as a carwash before he’s reanimated. There are rabbits who play cards. There is a keeper of the realm, blue sand and an hourglass that must empty before Pinocchio can return to his body.

Pinocchio’s fourth death occurs when he blows up the sea monster which swallowed his family. He enters the realm of the dead knowing Gepetto is drowning and impatient to get back to save him. The celestial keeper of this realm cannot send Pinocchio back to earth until the sand runs out of the hourglass. Only by breaking the hourglass himself and accepting the consequence of mortality, can Pinocchio return to save his father. Of course, Pinocchio does it. He smashes time. He puts his father’s life before his own. The miracle of the wooden boy that no one wanted is that, despite a life of immense suffering, he wants to go back. Despite only being given the smallest crumbs of kindness, he wants to give back.

For a Catholic, like del Toro, Pinocchio is a Christ figure. Crucifixion is overtly symbolized throughout the film. In the beginning, Gepetto and his original son Carlo, are placing a delicately carved depiction of Jesus’ crucifixion in the town’s church when a bomb hits and Carlo is killed. Later, Pinocchio (who is not delicately carved like Jesus, but made crudely by a drunken Gepetto) enters the church during service horrifying the village with his demonic presence. He is not Jesus and yet he sees a wooden figure, like himself, who is revered. He asks his father, “Why do they like him and not me?” It’s a question that is innocent and brazen at once. Innocent because it is asked by a child, who does not know the history or religious significance. Brazen because Guillermo del Toro knows what he’s doing. He pulls strings to elicit my reactions. He does it with finesse. He goes nuclear with the crucifixion metaphor near the end. The evil circus master, Volpe, places Pinocchio on a cross at the edge of a cliff and lights it on fire, growling “Burn Bright! Like a Star!”

It’s strange that an act as grotesquely violent as crucifixion could become impotent home decor or Jewelry. It’s absurd that del Toro needs to remind us, through a wooden puppet, how horrible this act is.

I am not a Catholic. I live in Europe but I’m not a cathedral buff. I don’t feel “wowed” by the architecture or impressed by how long it took to build. I’m not anti-cathedral, I just don’t care. I haven’t known many Catholics and those I have known are not observant. I remain very ignorant about all religions, including the one I was born into. I have no religious spirituality to speak of. It’s embarrassing to question God’s existence. It seems lonely to go looking for the answers at my age, and for now I’m too timid and frightened to probe more directly.

I am comfortable circling religion, riding an innertube on one of those lazy river waterpark rides, a safe distance from the molten center. In this religious adjacent place, I find meaning in art, in literature, in films. I find most of my joy here too. Much of my existence is anxious and sorrowful, but not most of it. Why mess with success? Don’t go chasing waterfalls.

When I watched Pinocchio on a cold afternoon, high on an adult gummi, there were tears streaming down my face. Pinocchio unlocked my deepest emotions. It’s hard to get to this spot when you’re riding the lazy God-adjacent river ride. I got hit with a jolt of religious ecstasy and the delivery system was Pinocchio.